Why Academic Science Needs a Technological Revolution

An account to why Liminal exists

In retrospect, it all started out so naïvely, so – for lack of a better word – unassumingly.

In 2021, in the throes of the global COVID-19 pandemic, with its White House press conferences and the flurry of public reactions and counter-reactions to public health information (and disinformation) and messaging all over the interwebs, my laboratory took one of those away-from-the-bench moments to work on a very small problem. Dane Deemer, a very talented computational biologist, had recently joined my lab, and he had an idea to solve a persistent problem – reliably collecting the data (and its metadata) from our analytical equipment in one place, for posterity. As it stood, as students ran the equipment, their sample and analytical data would end up in a panoply of digital domiciles (often, their own computers). Yes, there was a central, cloud location all this data and metadata should eventually wind up, but my students are busy people – and sometimes these files would not make it home before curfew.

No amount of shouting at the data could get it home. But Dane had an idea – maybe we could set up a system where, without any extra effort on a student’s part, the data from my gas chromatograph and its associated metadata would be automatically and reliably deposited. And maybe we could even offer some automatic analyses of this data type – used round-the-clock to measure short-chain fatty acids in my students’ fermentations - to help the students out. Dane had the chops to get it done – so he did.

We had no idea what would change at the time, but this small idea in 2021 launched a journey into the belly of the academic science beast (at least, the biological science form of this mythological creature), where we had to come face-to-face with the good, the bad, and the ugly of how my own laboratory was really functioning. Then we started talking to other professors about their labs and how they worked. We learned very quickly we were not alone.

“Economic dislocations, wars of conquest, terrorism, social fracture, corrupt elites, creeping authoritarianism, climate disruption, pandemics – these are a few of the themes future historians will have to make sense of in our present era.

We believe they will also understand our age as a time of crisis for expertise. Academics and specialists in one field wander into areas of knowledge that are not their own and issue public proclamations. Laypeople dismiss the guidance of experts and take advice from people who are not. For example, a remarkable number of people favor medical treatments hyped on social media over ones recommended by public health specialists.

What’s notable is that people know there is a crisis about expertise – its defenders and opponents alike. But they differ sharply about what the nature of the crisis is and how it should be addressed, either by individuals or society as a whole. This essay is an effort to make sense of one prominent idea that plays a fascinating role in these debates and controversies.

That idea is DYOR. (If the reader has not heard of it, we recommend: Do Your Own Research.)”

- Ballantyne, N., Celniker, J. B., & Dunning, D. (2022). “Do Your Own Research.” Social Epistemology, 38(3), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2022.2146469

In many ways, the COVID-19 pandemic is the clearest, lived example of erosion of trust in academic science. According to a recent study by the Pew Research Center, trust in “…scientists to act in the best interests of the public” slipped by 14 percentage points from its high water mark in April 2020 (the reader may remember this as in or about the Era of 15 Days to Slow the Spread) to 73% responding with “a fair amount” or “a great deal” of confidence. This is undeniably still a very high number; however, the interesting part is that it occurs against a backdrop of fifty years of near entirely stable trust in science despite declining confidence in many other institutions1. That is, despite a loss of trust in many U.S. institutions, science remained placidly immune, enjoying broad and bipartisan support among the public. A recent study undertaken by the National Academies’ Strategic Council for Research Excellence, Integrity, and Trust demonstrates convincingly that the loss of trust in science occurs in context of and relative to loss of trust in many other institutions2. This may give to some the comfort that things are not so bad – that there is nothing specific about science that is causing erosion of trust, but it is rather just caught up in an untrusting age. True as this may be, my takeaway from these results is a bit more dire – it is that science no longer possesses the imperviousness to decay in confidence it has so long enjoyed. It is clear that this response is polarized and responsive in individuals to political orientation, but this is neither here nor there; in the past, science enjoyed broad support across the political spectrum1. Confidence in science has rebounded somewhat in the last year – but it is still far from its pre-pandemic levels.

The most significant and palpable manifestation of this, I would argue, is the pervasiveness of exhortations across social media and interpersonal interactions to Do Your Own Research (or, DYOR).

Do Your Own Research (DYOR)

I first encountered DYOR in 2005 as a first-year PhD student, in a graduate immunology course. Inevitably, any introduction to adaptive immunology course covers the topic of vaccination and, in turn, the Wakefield studies and his supposed link between the MMR vaccine and autism (tl;dr – the paper was retracted by The Lancet3 and the vast preponderance of evidence does not support this connection. That’s as generous to the opposing position as I can be.). However, the 1998 result was seized upon by celebrity influencers with deep personal connections to autism but dubious medical and immunology expertise.

WASHINGTON - JUNE 04: Jenny McCarthy, author of the best-selling book "Louder Than Words: A Mother's Journey in Healing Autism," talks to the audience at the Green Our Vaccines press conference in front of the U.S. Capitol Building on June 4, 2008 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Paul Morigi/WireImage

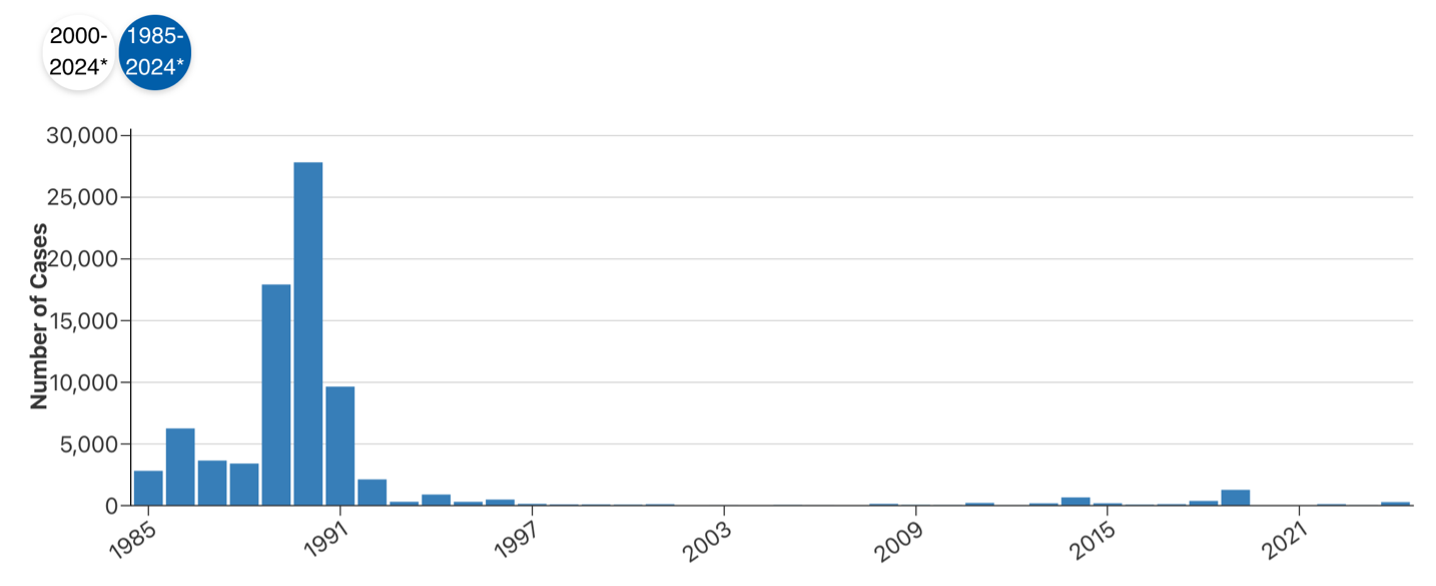

This influencer advocacy strongly encouraged Americans to DYOR. And despite the lack of evidence in the MMR-autism link, 24% of Americans still believe that the vaccine causes autism, and another 3% are not sure. This, in turn, caused MMR vaccination rates to drop. And, some would argue predictably, this caused measles cases to come back. The CDC reported 284 cases of measles in 2024. In fairness, let’s keep this in historical context:

Data and image: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/index.html [accessed 1/11/2025]

It’s nothing like the 80s, with thousands of annual cases. But it is profoundly not zero. Given that measles is widely known as a strong – perhaps the strongest – contender for the World Contagion Championship, any cluster of measles cases has serious outbreak potential. Note also the trend. For nearly a decade, measles cases were actually zero – so pervasively so that the CDC declared measles eliminated in the U.S. in 2000. Eradicating the mind worm that the MMR vaccine causes autism has been substantially less successful than the vaccination campaign.

“It's a dangerous business, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

- Bilbo Baggins to Frodo Baggins, The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien

Profoundly, DYOR is not the primary cause of the crisis of expertise that Ballantyne, et al, describe, though it may cyclically reinforce this crisis. It is not without its benefits – we desperately want an educated and informed society that can understand and act on the latest scientific information. Frankly, many intelligent people without a significant background or training in a scientific field can learn it as well as the experts (the experts were not always so!), given enough time, dedication, and access to information. I use DYOR in the pejorative sense, however, when a lay researcher does not invest the required time and energy to establish the required expertise before declaring oneself capable of evaluating the information. The exhortation to DYOR in the zeitgeist does not carry with it the admonition to deep and careful study. Rather, it says to the reader on social media: “You, too, can be an expert on this subject with just a few Google searches. You do not need anyone else to process this information to make an informed decision. Just Do Your Own Research.” I submit instead that this type of DYOR is a symptom of the planted seeds of distrust that eventually germinated, grew, and blossomed, destroying the perpetual immunity to institutional trust decay that science had enjoyed in the U.S. for decades.

“…we desperately want an educated and informed society that can understand and act on the latest scientific information”

Although it also reports that 47% of people think scientists view themselves as above others, one bright spot in the Pew Research Center report is that intellectual humility on the part of scientists can help rebuild trust in science on the part of the public. However, the authors also found that it is important how that humility is expressed. We submit that the process of expressing humility and rebuilding trust begins by saying the quiet part out loud and being clear about how the present system currently functions. It continues in making the required changes to sweep away the seeds of distrust that we see and build a better system. We further submit that this will require technological revolution in the academic science laboratory.

We did not intend to address trust in science or DYOR or any such thing when we first set out on this journey. We intended to take one small step to increase our trust in our own science, by making sure the provenance of one type of data was secure and its analysis reproducible, and without requiring students to remember one more step. But the more we looked, the more we found the seeds of distrust scattered in our own laboratory. When we talked to others, we found that the seeds were planted in their laboratories, too. We took one small step after another to find solutions to banish these seeds from our laboratory, and we eventually looked back and found we were far down The Road on an unexpected journey – and that journey became Liminal.

“We intended to take one small step to increase our trust in our own science, by making sure the provenance of one type of data was secure and its analysis reproducible…”

Over the next however-many weeks, we will walk through our path on this journey – what we saw in ourselves as well as in others, where we see the need for systemic change. We’ll describe where we have found incredibly smart, incredibly well-intentioned people (sometimes, us) make decisions and take actions that cause distrust in science. And we’ll advocate for a new way forward that we think will drastically improve our confidence in our (and each others’) science, building more and better knowledge with the resources with which the public entrusts us.